Phil Pearlman has four, simple rules he developed regarding long-term health and wellness. I started thinking about this in a response to a tweet about financial advice books. The laws of financial health are equally simple. Simple does not equate to easy, though. What is hard is consistency, execution, and discipline. Our brains just don’t see money as simple and easy.

Financial Health is a Confoundingly Simple Process

SPEND LESS THAN YOU MAKE. However, if you want to execute this well, most people must make this automatic. Our society has evolved to one that consistently and constantly encourages you to spend. Every ad. Every bank. Every investment firm. Borrow and spend. Invest and spend. Yes, you can afford that car, vacation, or house. Maybe you can stretch your cashflow to make the payments. But in doing so, did you limit or eliminate the ability to save? Whether those payments are affordable depends on what else you might want to accomplish. Maybe this purchase makes no sense if you want to be able to quit working in 20 years - because the savings and compounding are needed for that goal to be achieved.

Understand how much saving is needed to achieve your goal. The key here is to know what financial independence means to you and when you want to achieve it. What does “funded contentment” or “enough” mean to you? Align the investment strategy with the timeline for the investment and also with your ability to deal with the swings in value that inevitably occur with every investment (technically, risk/volatility tolerance and risk/volatility capacity). This means you might have multiple buckets of money for multiple goals. The really hard part of this is understanding yourself and determining what funded contentment really means. To you.

Maintain sufficient cash reserves. There will be a time when you need cash and the market is down. The only way to avoid taking a loss at this juncture is to have a cash reserve. Your cash reserve amount is highly dependent on your specific situation. Emotionally, cash reserves make you powerful. When you know that it would require a truly exceptional, significant disaster for you to become insolvent, mentally you become extremely strong. And as you may have noted, your ability to stay invested during the worst markets is what drives compounding.

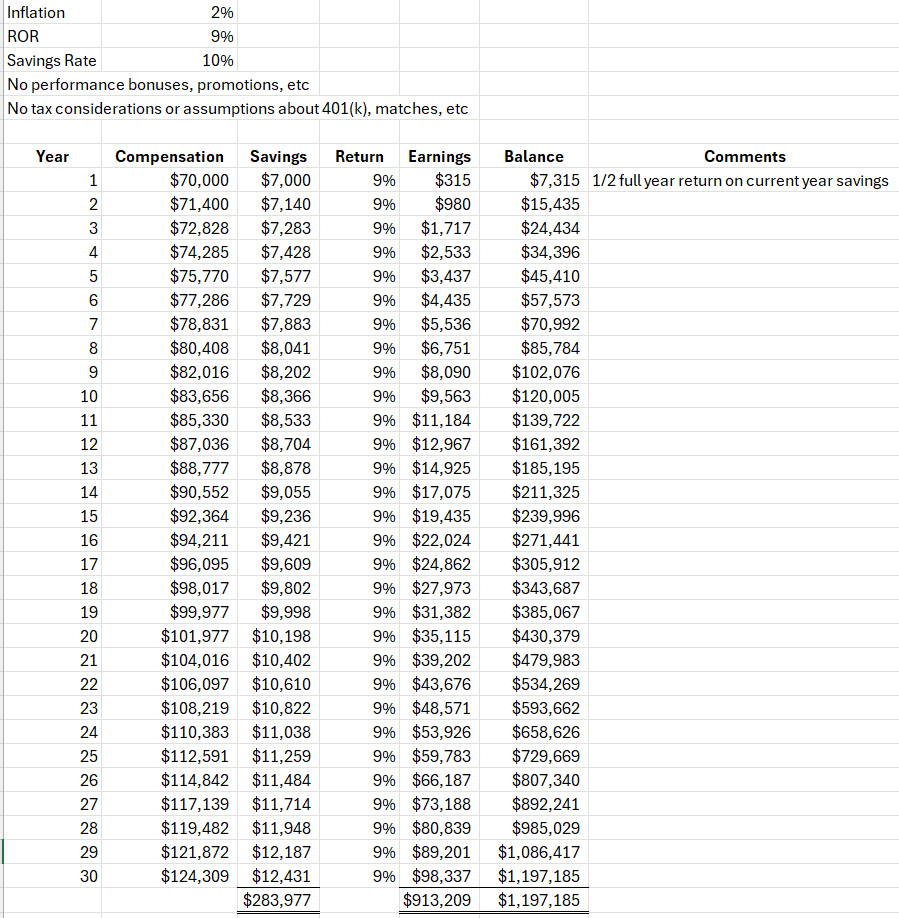

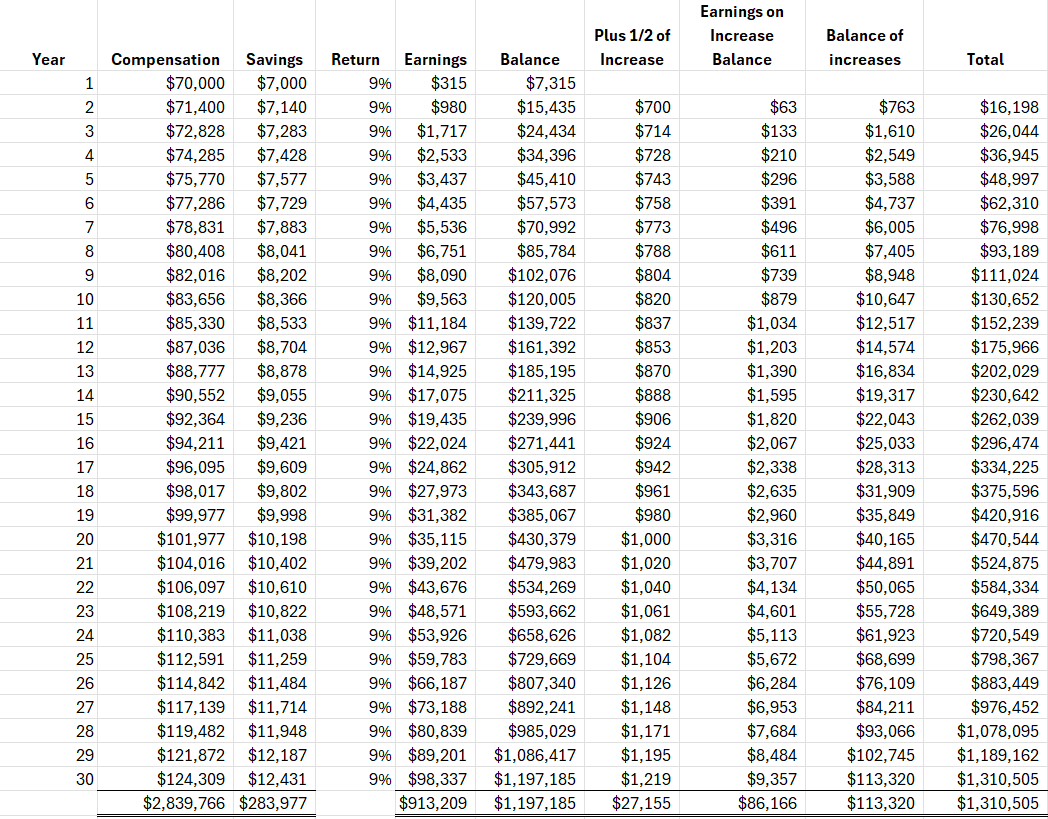

Systematically and automatically save and invest. Whether it’s every week, every time you receive compensation, annually, or anything in between, I don’t care (although my belief is more frequently is better - mathematically, you want as many dollars compounding as early as possible). Use a system and take away the decision of: “Should I save, now?” Instead, save always, and never ask the question. Do the same with the amount, make it fixed and automatic. Invest the funds automatically, as well. Do not force yourself to evaluate your investment strategy every time you make a deposit. Do you need to review your strategy? Yes (although many accounts have done quite well when completely untouched for long periods). Like once a year. You may change it over time as your circumstances and ability to tolerate volatility change. I am also a believer in the value of rebalancing when your allocation drifts, and it will drift. Allocation drift occurs naturally as returns compound at different rates for different investments. And, again, this is something best done by rule, automatically, in my opinion. Introducing our brain into the process is bound to create, for most people, suboptimal results. I’ve illustrated the value of saving 10% of compensation and not interrupting it. By the way, the S & P, since 1970, has returned 10.8%, compounded.

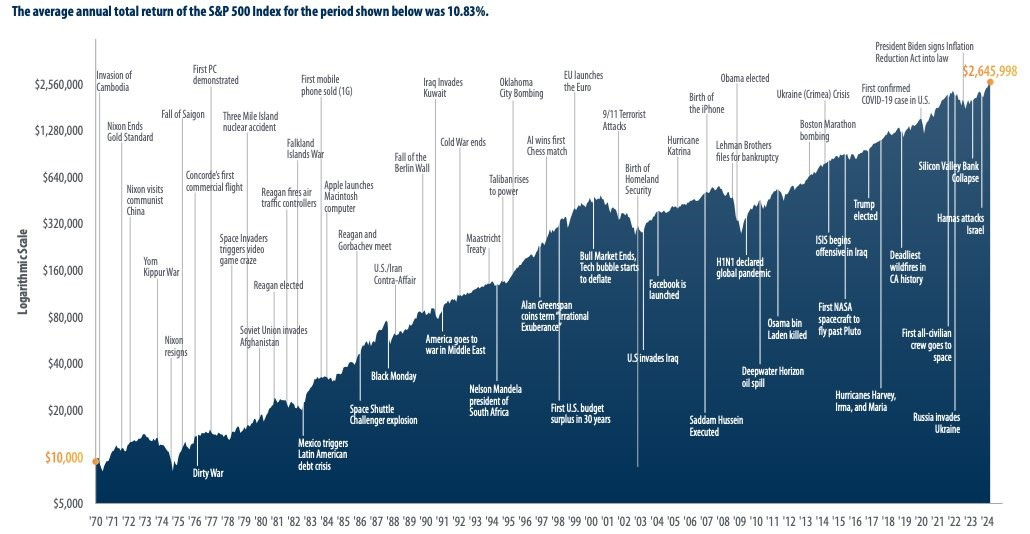

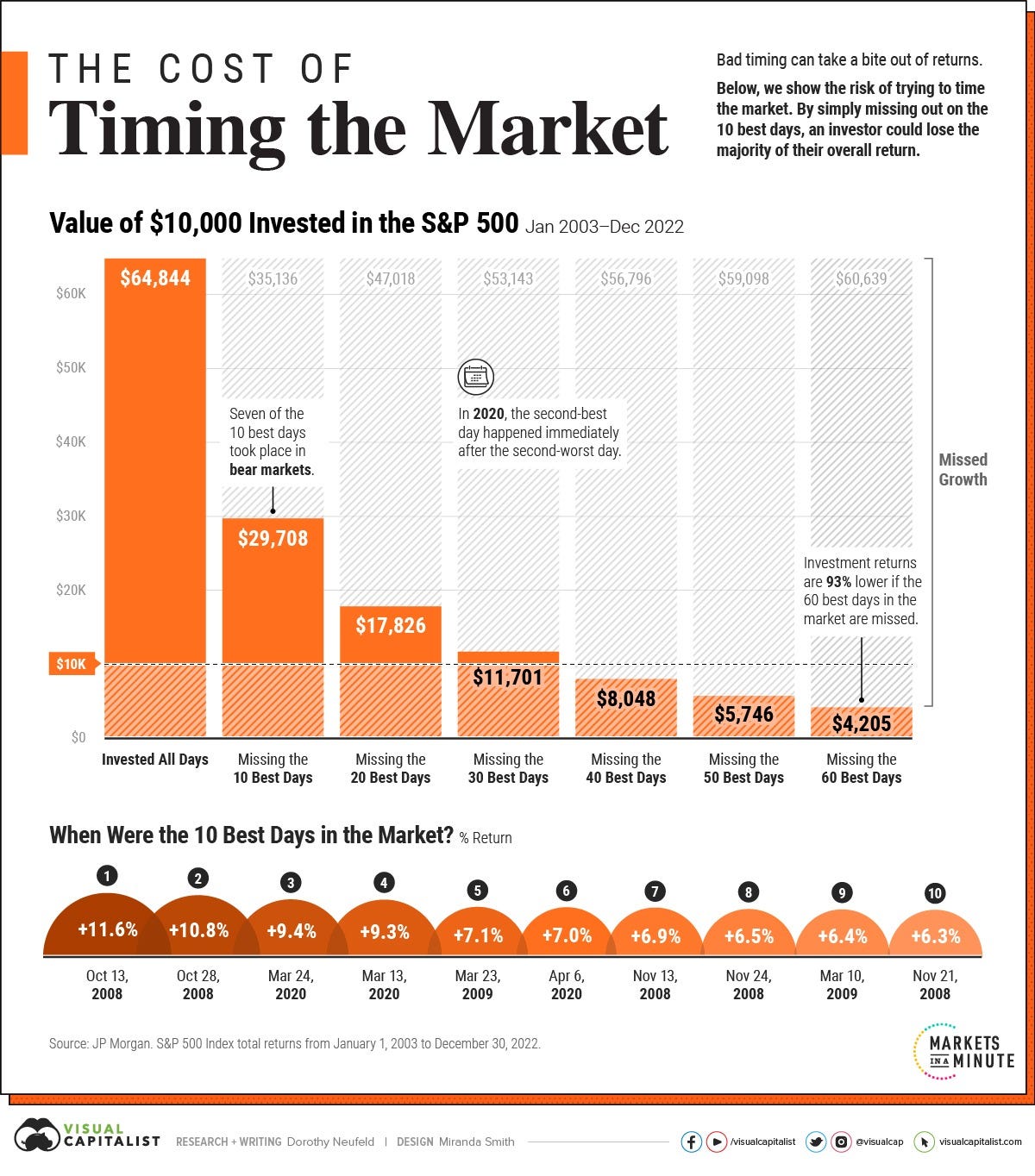

In this example, the first $100,000 took 9 years to build. The second $100,000 took a little less than 5 years. The third $100,000? A little less than 4 years. Because compounding.Never interrupt compounding (see above!). Compounding requires patience and an acceptance that most people (including you, and definitely me) cannot time markets. Markets are volatile and statistically appear to be a random walk. As you can see below, there is always something happening in the world that is scary, amplified by the media, and a “good reason” to either not enter or exit the markets. Also, when you exit, which is one decision, you now have another, difficult decision: when to re-enter. If you are not invested during the high performance periods, you will not compound well and may not compound at all. The related action here is avoid trying to time markets. This is incredibly hard to do. Things happen every day that are scary, and the media gets paid to comment and provide “advice”. Note that no one in the media earns their living serving clients. This is precisely why the real advice we give you is difference from the media forecasts, pronouncements, and media/pundit ‘advice”, even when it comes from what appear to be (or perhaps, heretofore) successful investors and asset managers.

Here is an illustration of what happens when you interrupt compounding.

It is Equally Complex Emotionally

Thinking about this a little more illuminates some other financial health fundamentals:

Ignore what others are doing. I’m old, and we used to call this “Keeping up with the Joneses”. I think it’s “evolved” to FOMO now (which, and it might be this week’s sign of the apocalypse, can now be found in Miriam-Webster, here). Have your own plan, understand your own desires, work your plan. I am definitely not saying “don’t own a Porsche”. If that is what gives you core happiness, by all means own one. However, my opinion is that you should purchase things like this within the context of your spending plan. Make sure that other things you want to accomplish can be funded, as well. Unless you want to live out of the car and retire in it! That is a plan, too, by the way.

Be cognizant of your emotions and ingrained behaviors. If you experience feelings of panic when the market drops, you need to find a way to manage that. I do not mean you need to stop feeling the way you do. You need to find a way to recognize what you are feeling and evaluate whether how you feel is helping or hurting you. In my experience, the most wealth-crushing decisions occur in highly emotional moments. Take the time to reflect on how you feel, and why you feel that way, before acting. There is not a single thing wrong with panic, anger, or sadness. You will and should allow yourself to experience and feel your emotions. But don’t invest or divest when you are “in a mood”. The outcome tends to be less than positive. Kicking yourself later only makes things worse.

Save half of your compensation increases (at least). Lifestyle creep is one of the most destructive things, financially. Warren Sapp (read it here) made $77 million in the NFL. He was earning over $100,000 a month post-football. He declared bankruptcy. Pay attention to lifestyle creep - very few of us avoid it.

Have patience and stick to your plan. When you are most fearful is often the worst time to make changes. That’s not to say your plan never changes. It constantly evolves. Everything changes. You initial plan is probably “wrong” a month after it has been constructed. The point of having a plan, ideally with multiple scenarios, is to be able to reference where you started, define where you want to go, and identify alternatives should certain events occur. Then process-wise, we like to see an annual plan update and review. This way you can both track progress and adapt to changing conditions.

OK, Now What

That’s it. These are the fundamentals. There’s no need to make it complicated. Do the basics. Here’s some reinforcement from Shane Parrish, who is devoting his life to clear thinking. He’s written a book on this topic (find it here).

On Rule #1, I am always reminded of Micawber's speech to David Copperfield (the context is that Micawber has just come out of debtor's prison and is rather loosely based on Dickens's own father who also was imprisoned for debt when Dickens was a child):

"Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure nineteen six, result happiness. Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure twenty pounds ought and six, result misery. "

Dickens lived by himself for about 6 months in London while working at a blacking (shoe polish) factory while his parents were in debtor's prison. (Micawber is Copperfield's landlord in London, so this section of the novel is closely based on Dickens own childhood).