The Accident

Investment Risk and The People Who Have It

Experiencing investment risk is no accident, just as this accident was, before it happened, a risk (as is everything else mentioned by Mr. Prine in this song). We also call upon James Taylor and Bob Dylan in this conversation.

The world of financial advice makes extensive use of the word “risk”. What advisors are referring to, when talking about risk, is, in most cases, volatility in value/price. In all markets, there is volatility, in that the value of a given investment, either broadly: triple-A rated municipal bonds, or specifically: Minnesota Taxable 06.25% 07/01/2053 Residential Bonds Series 2023, for example, rises and falls each day depending on many factors, including demand for the security, interest rates, flows in and out of that particular market, and buyer/seller confidence.

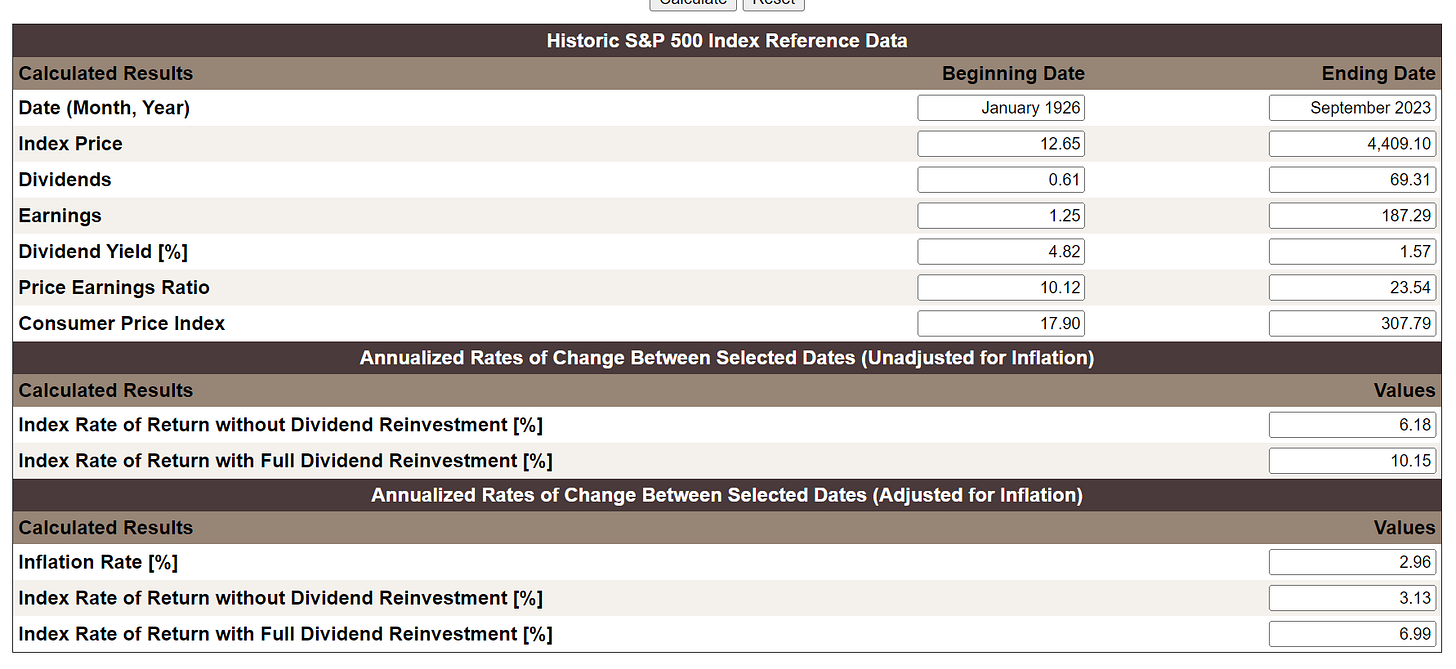

That’s because all you tend to notice is the (temporary) reduction in value that occurs every single year. It’s volatile, sure, and at the same time you see a steady, if inconsistent, increase in value, which equates to a compounded rate of return, if reinvesting dividends, of 10.15% (6.99% if adjusting for inflation) since 1926. In absolute, un-inflation-adjusted dollars, your money invested here doubles about every 7 years (see the Rule of 72 here).

Risk, when it is defined as volatility, is as near a 100% probability as is possible in your investment portfolio, particularly when it comes to the US stock market. It’s pretty much a certainty. At the same time, mathematically, it is a risk. It’s just that this is an awfully predictable one in terms of frequency of occurrence - but not in size.

Definition(s)

What non-professional investors (by this I mean people who do not operate in the investment markets every day - I’d say normal but there is no such thing as a normal person) mean when they talk about risk is:

“Will I lose some or all of my principal?”, and

“What is the likelihood that if I don’t lose any principal that I will make some return?”

Mostly, “normal” people are thinking of the first bullet. Another definition of risk, from Carl Richards (although there is no way to mitigate all risk, because I doubt there is a way to think of every risk):

“Risk is what’s left over after you think you’ve thought of everything.”

And last, both amusing and accurate, is Jason Zweig’s definition:

“The chance that you don’t know what you are doing when you think you do: the prerequisite for losing more in a shorter period of time than you could ever have imagined possible… In the end, risk is the gap between what investors think they know and what they end up learning - about their investments, about the financial markets, and about themselves.”

Risk, however, comes in many forms beyond volatility. As an investment and financial advice professional, I have to worry about these, in most cases for our clients, since our clients are unlikely to be cognizant of most or all of this.

Man, That’s A Lot of Risk(s)

Market risk, because we have no idea what any given market is going to do on any given day. Statistically, this is a random walk.

Liquidity risk, resulting when you need cash but cannot immediate generate it from the particular investment, which could be for a variety of reasons. Investment real estate is a good example, as there are times when you either cannot sell it or, because there is a real estate recession, you do not want to sell it. If you need cash, you might be forced into a sale at the bottom of the market or perhaps have to borrow at a poor rate, presuming there is sufficient equity and your balance sheet and cashflow support a loan.

Concentration risk, whereby you have a large percentage or materially large dollar amount in one single investment or perhaps one country or sector. This might occur due to the tax tail wagging the dog or endowment bias, for example. And if this particular investment performs poorly, or worse, does a Circuit City Stores, Inc (painful, personal experience, although there are many examples), which happens fairly often, you literally can lose significant principal.

Credit risk, which might show up in your portfolio should a bond issuer fail to return your principal or make interest payments, and you might own investment funds that invest in various debt instruments.

Reinvestment risk results when one investment turns or creates cash and you wish to reinvest that cash. As am example, if you had thirty year bonds maturing during the long zero interest rate (ZIRP) period, you could not reinvest those dollars at a comparable yield in a comparable risk product, and for the most part the difference was often 5% or more in yield.

Inflation risk, where inflation reduces the purchasing power of your investment(s). During the ZIRP period, this was a non-event, and as we emerge into a higher-rate environment, it causes real loss of purchasing power.

Political risk results when political actors legislate a given outcome, such as nationalization of the oil companies in South America.

Counter-party or default risk results when another party in a given investment strategy, such as where you have lent your stock to a short seller, fails to produce when called upon and in this case fails to return the shares you lent.

There are a whole bunch of cognitive biases that can exacerbate or create risk:

Home country.

Anchoring.

Confirmation.

Endowment.

Plenty more.

This is not a comprehensive list. It is reasonably complete. The word “risk” addresses many different components in an investment, and while what may take precedence your brain is “Am I going to lose any or all of my principal?”, there is much to consider on the risk side of any investment that is likely to improve your investment process. What’s a poor boy to do?

Managing Risk

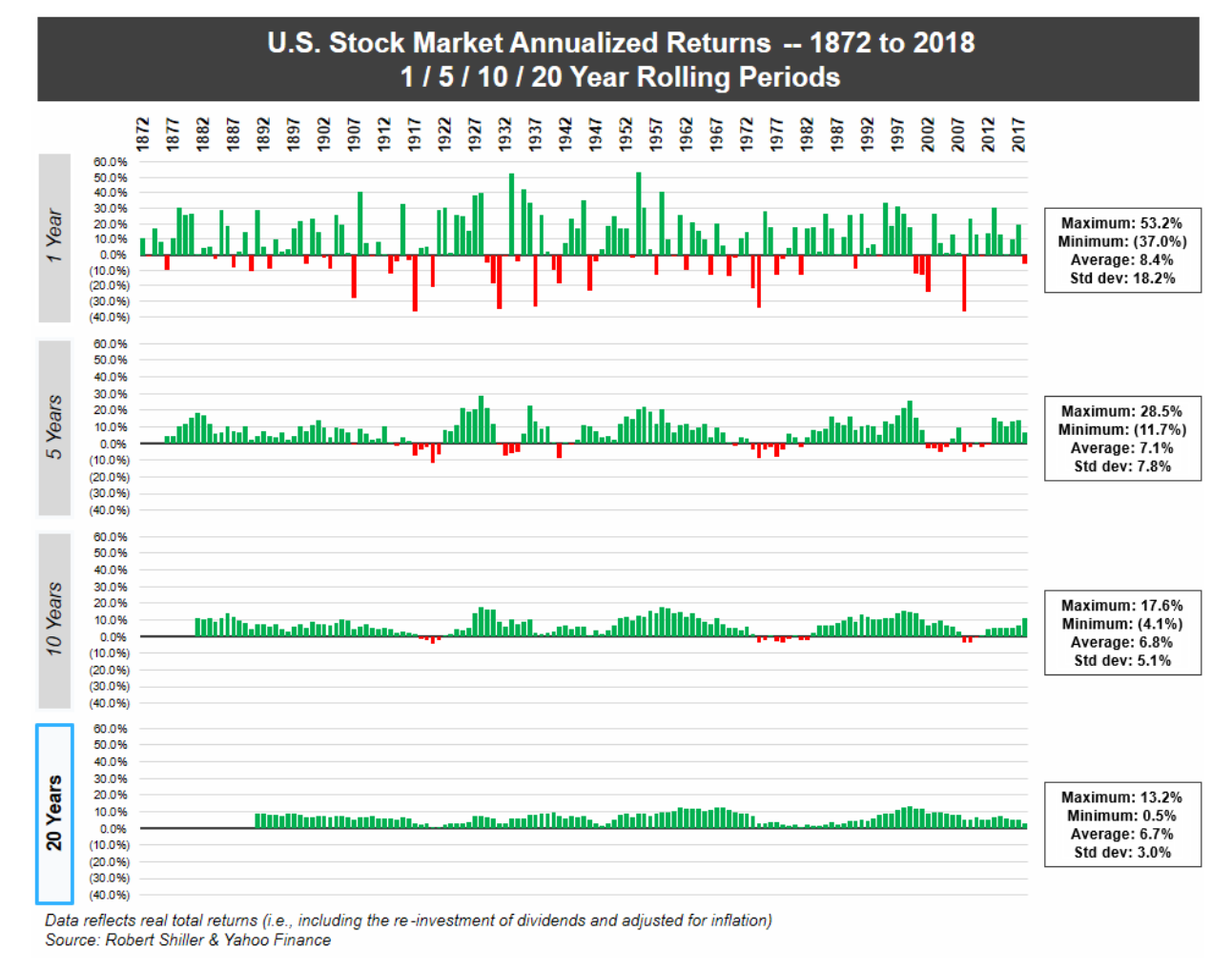

You can certainly ignore risk if you wish, and there are risks you can reasonably ignore if the result of experiencing the risk is immaterial to your desired outcome. If you simply have a somewhat diversified portfolio composed of the S and P 500, and you have 20 years or more to be investing, the probability of principal loss is quite low. This chart shows you that there is almost no chance of losing principal in a rolling 20-year period. So a big part of managing US stock market risk is a willingness and ability to leave money in this market for as long as 20 years.

However, if the risk is material, regardless of probability, you should devise some mitigation, if possible. But it’s a low probability, you say? Understood, and yet a 1% probability risk happens to someone (there are, roughly, 336 million people in the US, so 1% of us is 3.6 million people), and if it’s you, and you cannot afford that risk, the probability is of no consequence. For you, it happened. If you wish to avoid desolation row, though, I believe it paramount to manage your risks.

Pre-mortem analysis helps you identify potential failures and create mitigation plans.

Position sizing is needed to understand potential impact. This is both a quantitative and behavioral assessment. I know plenty of people who could afford to lose (pick a number) $X, yet they would be devasted if they did, even though they would be remain financially sound. Think through what you can stomach as well as what you can afford.

Probability is a factor, although it is, itself, behaviorally problematic. Our emotions tend to convince us that low probability events (and what constitutes “low” or “high” is different for each of us) will never occur and high probability events are guaranteed to occur. Neither of these is true. My father smoked for 75 years. Never had any form of cancer, and everyone figured cancer would be his downfall. He died after a bad fall at age 100. He ignored the fall risk associated with anemia, which is quite high in the risk profile of the elderly. Low probabilities with high impact deserve more attention, in my opinion, than high probabilities with low impact (high/high is awfully obvious). How much risk you are willing to carry is directly related to the impact of the risk occurring. And that’s not generally the way we humans think.

Contingency planning provides the tool to consider what you will do if a risk becomes a reality. Pre-mortems help you identify contingencies.

Mitigation/hedging can be as simple as having the right amount of insurance. Now, with most investments, installing a hedge reduces your upside or limits your downside, at a cost, both in dollars and complexity. Unless you are trading options, and even if you are, this might not make sense. The best mitigation is to diversify away as much risk as you can and then size your positions such that one failed investment is immaterial to your outcome. The behavior problem with diversification is this: A properly diversified portfolio will almost always have a segment that is underperforming, and this is hard to cope with emotionally.

An Easier Approach

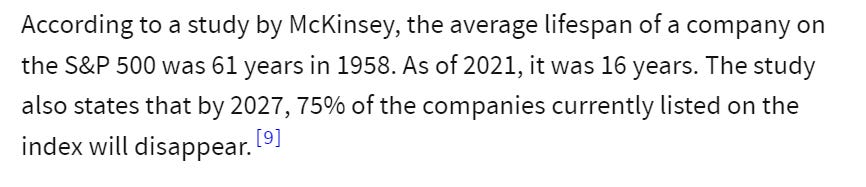

Sure, you can build a risk management process. You can spend time on quantitative and qualitative measures and on behavioral issues. Can you be successful in a single category? You can. You have seen that investing in the S&P 500, over twenty year rolling periods, can be a really effective strategy. Nick Murray is a huge proponent of this strategy (with a five-year income reserve, too!). You have also seen that diversification within a single category matters, as many companies within the S&P won’t be there in 15 years, and if you are concentrated in the wrong ones, well, this strategy will not work. There are plenty of people who invest in real estate and live off of that income, and again I suggest a significant income reserve here.

Or you can do what works for most people:

Consider your behaviors: Are you patient? Can you stomach large drops in value?

Understand your risk capacity: How much could you lose and still be OK?

Define your time horizon, and you might have more than one. If you are saving for a second home, maybe that’s 5 or 10 ten years. For your financial independence, maybe that’s 10 or 20 years, with a 40 to 50 year income need following that, for a total time horizon of 50 to 70 years. Sound crazy? I do this every day. My dad lived to 100. We have other clients in their late 80’s and early 90’s.

Create accounts matched to your goals and risk profiles for those goals.

Diversify across investment categories (the financial community calls them asset classes), and yes, this includes your real estate investments.

Maintain an income reserve consistent with your risk profile: More risk = more income reserve.

Routinely rebalance your portfolio to maintain your risk profile. Once per year is generally sufficient.

Use your income reserve to avoid down markets, and be prepared to sit on some investment selections for ten years or more.

If this is not something you want to spend time on, or is not within your skill set (and you don’t wish it to be), consider hiring a professional. I am obviously talking my book here, and at the same time there are both really good reasons why people hire financial advisors and significant data supporting the value great advisors can bring to great clients.

What’s right for you? That all depends on your psyche, your time horizon, your desired outcomes, your skills, how you wish to spend your time, your savings capacity, and your capacity for risk.

I hope this has been useful for you. All feedback is a gift.

Sundry:

Glad to see my friend Kian back on Xwitter. You can find him on LinkedIn as well:

Bob Seawright is also back, thank goodness:

I’m a fan of behavioral finance. Here’s an event, the BeFi Summit, worth attending: