Is it live, or is it Memorex? Do we ever know that’s going to happen next, or have we been fooled by any number of biases, prejudices, and experiences?

“Nobody knows anything...... Not one person in the entire motion picture field knows for a certainty what's going to work. Every time out it's a guess and, if you're lucky, an educated one.”

William Goldman, Adventures in the Screen Trade: A Personal View of Hollywood and Screenwriting

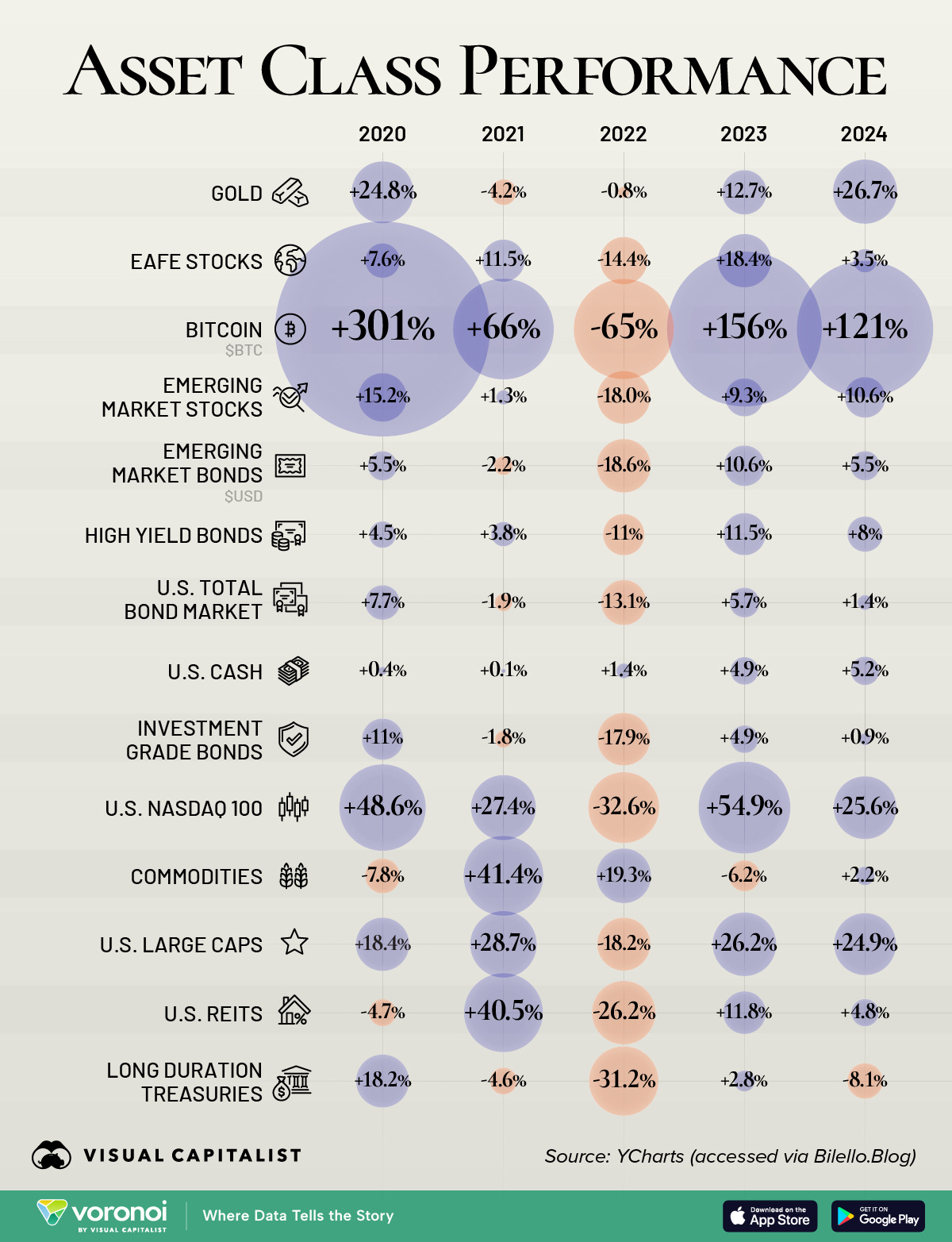

I ran across the below graphic yesterday. What does it say? Well, how did you you decide to read it? Was that a conscious or unconscious decision? Was it both conscious and unconscious?

The bubbles look awfully attractive for Bitcoin (here’s my favorite piece on this topic). I’m not sure I’d call it an asset class, but hey, we all have opinions (and like feet, they often stink, but that’s not our topic today). Look at those yuge returns!

We do not, however, experience returns this way. Not most of us. We experience them in real time, not looking backwards 5 or 10 or 20 years. Thirteen times your money in five years? Gimme a ton of that (in hindsight). This of course assumes you bought at the open, 1/1/2020, and sold at the close, 12/31/2024. If you did not, then you experienced something else. And you don’t have fungible dollars, you have Bitcoin priced in dollars. You have to exchange the Bitcoin for dollars, or some fungible currency, to buy just about anything and to actually realize your gain in a spendable way. And… you would have had to survive 2022, when the theoretical starting value of $6.66 (yes, each $1 of your BTC had grown to $6.66 in two years) dropped to $2.33 by year-end. HODL, indeed.

2022 was one of those years in which nearly everything had a temporary reduction in value (if you did not sell, it was temporary. If you did, ouch, and I hope you re-entered the market immediately). It was an extraordinarily difficult year to sit through the drawdown, especially when everything else was dropping, pretty much daily, significantly. I am not busting on BTC here. It’s an example that what we “know” in hindsight may be dramatically different from how we experience and “know” something live.

We also cannot know what will happen in the future. Much like quantum physics, all of life is uncertain, all the time. One of the great mysteries (some would call it mysticism) to most of us is the concept of superposition. The famous (well, to physics geeks it is) Schrödinger’s cat thought experiment, where a cat can be considered both alive and dead until observed, is often used to express the concept. So why, exactly, do I bring this wacky subject up? Because now we have the latest reason to worry, the Federal deficit (or is the Iran bombing?), which seems to arrive at a worrying point every few years. Is it a point to worry about, or not? Well, it depends on when and how you measure it, so you can argue that superposition is in play with our financial system.

Jamie Dimon and Ray Dalio (both mentioned in the above-linked Wall Street Journal article) are two of the more famous non-members of the Forecasters’ Hall of Fame - which if you’ve read any of my work infamously has no members. They are charter members of the Forecasters’ Hall of Shame (if you equate shame with being incorrect). They are prolific forecasters and to-date prolifically wrong in their expressions of future, dire consequences, and they are always dire. Outcomes perceived as unusual, surprising, unexpected, or highly negative send our twitchy brains into mostly subconscious, reactionary overdrive, whether it be “squirrel!”, “tiger!!!”, big, fat nothingburger (most probable), or actual disaster (not often, although even events such as WWII, for example, so far have been both recoverable and onward and upward). Now, I have no way to know if the D square forecasters are right or wrong this time or any time - only the future tells us that - which, given the number of variables (hey, we gonna have a big war in the Middle East or a little one, for example, or is the woefully elected Trump actually going to become America’s Hitler?), we cannot know. But we humans are linear, projection-driven, recency-bias thinkers in a probabilistic world, and that, at least right now, ain’t changing. So we got what we got.

A benchmark for everything

The yields on Treasuries set a baseline on borrowing costs across the economy because the U.S. government, for all its challenges, is still seen as the safest borrower around. The yield on the 10-year note, in particular, is a major determinant of 30-year mortgage rates.

We can (do?) find something to worry about, be it inflation, devaluation of the dollar (it’s not depreciating, Mark, other currencies are appreciating!), or dropping bombs on Iran. Why are we always finding something financially worrying? Drawdowns, that’s why. They “make” us worry (we choose to worry, actually, whether we know this or not).

“Drawdowns don’t matter”. Now that is a powerful statement, although I take exception to the “loss” wording in the definition of drawdown, since a drawdown is most probably a temporary reduction in value - unless you sell. They certainly matter emotionally. I have never met a client who is comfortable during any significant drawdown. When we are talking about performance with clients, we always discuss drawdowns. Mr. Hagstrom is right in the sense that long-term performance, whether you are in a concentrated strategy or not, will encounter drawdowns, and that in the longer term a drawdown is inconsequential. And, at least so far, not only have you recovered, you’ve outperformed simply by staying invested. Where drawdowns matter is in your behavior. You must be comfortable either closing your eyes, ears, and mind when drawdowns occur or you must both comprehend and feel that drawdowns are a part of the process and the net result (we are talking at least ten years here) has always been, historically, positive. Is this time (the next drawdown, that is) different? Well, it could be - this is absolutely true. The problem? Every time this has been said, and it’s been said countless times (like in April of this year), it has been incorrect.

To expand just a touch on one of Mr. Hagstrom’s statements, Google news events for the last 80 years. There are an astonishing number of reasons not to invest or to exit the markets or to dig a hole and go all prepper. And you’d be far poorer as an investor if you’d paid attention to any of them. Capitalism works and has worked. It’s not a good system, of course. There are winners and losers. People get hurt in the process. People with big hearts hate the “lose” part of capitalism. It’s just better than every other system we’ve seen these last few thousand years.

So, guess what? Nobody Knows Anything. Not exactly helpful, right?

What Is Helpful?

Do what has worked over these last 100 or so years. This is remarkably boring and consistent, and I am hardly the only person saying these things. You want to build endurance? Do your cardio. It ain’t rocket science, people. That does not equate to easy. Simple. Not easy.

Understand what funded contentment means to and for you and for those you care about.

Save more than enough and do this first. Have fun spending the remainder! And if you “oversave”, I have confidence you - you can find a way to unload that excess capital. No one I know has ever complained about having too much money later in life. What you cannot do is (legally) manufacture cash later, when you need it and don’t have it. This does mean you need to understand your current and future cashflow needs, as best as is possible and understanding things will change. At the same time, do not starve yourself now in the hopes of eating well tomorrow. Life is fickle. It can end in an instant. Conflicting advice? Perhaps. But not if you focus on those things you really care about.

Save systematically and automatically. Take decision-making out of the saving process. Your brain will often find a way to spend your cash if you allow it to do so.

Consistently and repeatedly model your financial needs. Yes, it’s a math/modeling exercise, but at its core it’s a behavioral exercise, which is why we start with the funded contentment work. The repeating discipline and process are incredibly important.

Maintain a cash/income reserve consistent with your circumstances (somewhere north of 3 months’ expenses, in my opinion, and it could be 3 years or more). Personally, I hold 4 years’ cash, and that is because my employment is ending this year and I am risk-averse. There is no “right” answer here, as is true with most financial planning questions and answers. It’s all about you, baby.

Utilize a consistent investment strategy. I tend to prefer diversification and a core/satellite approach. This is no recommendation. There are many successful approaches. Once again, the repeating discipline and process are critically important. My experience is the more concentrated you are the more careful you have to be about when you might generate cash, exit, or change your strategy, or you may want to hold more or less cash. Once again, there is no “right” answer. The key is to understand your cashflow needs and design, implement, and stick with a process and investment strategy to meet those needs.

Maybe, just maybe, you’ve heard all of this from me before. Well, accuse me of emulating Jason Zweig, who, I am paraphrasing here, would comment that his genius is finding maybe 50 good ideas and then finding ways each year to restate or repackage them. Guilty as charged.

Love it Mark. Great stuff.